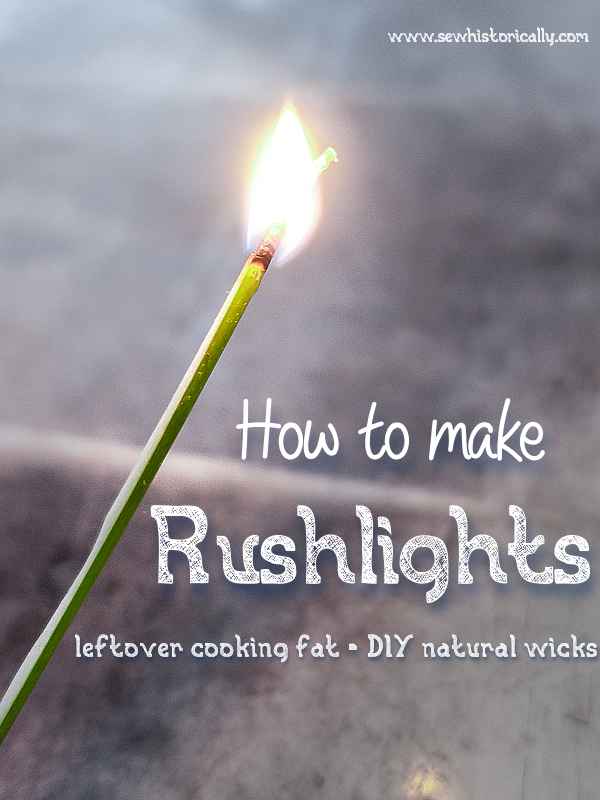

Learn how to make rushlights with leftover cooking fat! You can use this DIY bacon fat candle with a DIY natural wick as emergency candle or as eco-friendly alternative to store-bought candles!

‘”I have no more influence than a farthing rushlight.” “Well,” was the reply, “a farthing rushlight can do a great deal: it can set a haystack on fire, it can burn down a house; yea, more, it will enable a poor creature to read […] Go your way, friend; let your farthing rushlight’ shine. (The Christian Miscellany, And Family Visiter, 1868)

Rushlights are one of the most ancient forms of lighting: They were already used in the Roman Empire and they were still used in the late Victorian era, especially in working class households. Rushlights were a cheap alternative to candles: They were usually made at home by children, women or older people.

Rushlights are really easy to make: You can still make them today as eco-friendly and cheap emergency candle. Besides, rushlights are a great way to use up leftover cooking grease! All you need to do is to gather rushes in summer or autumn, peel and dry them and then dip them into cooking grease or tallow.

‘Rush-lights are made in the same way as dipped candles, only having the pith of a rush for a wick instead of cotton; they require no snuffing, as the burned wick falls off as the tallow consumes: hence they are used to burn all night in bedchambers.’ (An Encyclopaedia of Domestic Economy, 1855)

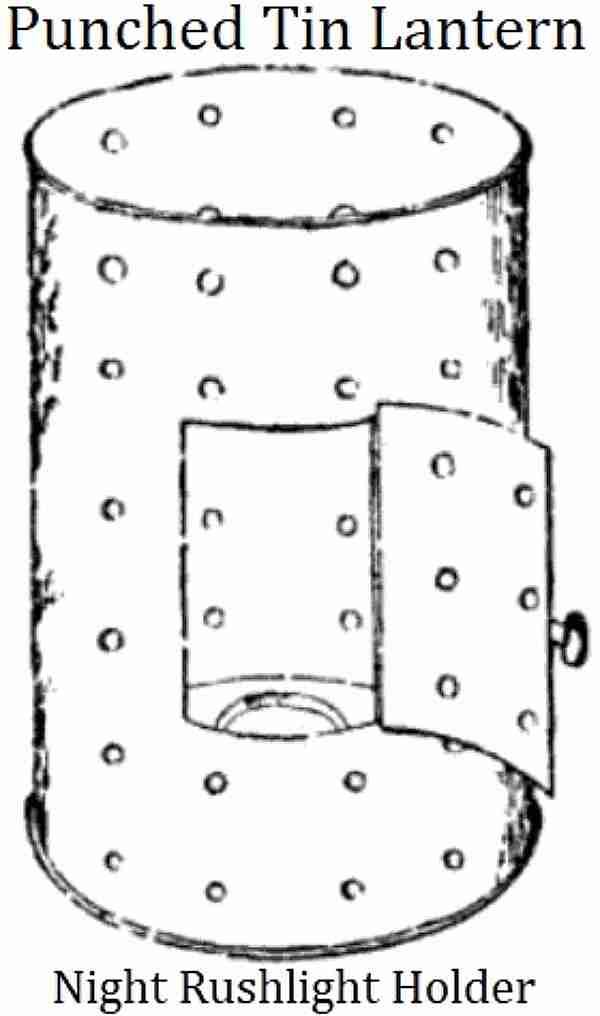

Rushlights were often used as a nightlight because, unlike candles, they were safe to use. Apart from that, it was difficult to strike a light before the invention of matches. In the days of the tinderbox, the rushlight was kept burning all night in punched tin lanterns so as to easily light a lamp during the night and start a fire in the morning.

Where To Find & When To Gather Rushes?

‘The proper species of rush […] is to be found in most moist pastures, by the side of streams and under hedges. These rushes are in best condition in the height of summer, but may be gathered so as to serve the purpose well quite into autumn. It would be needless to add that the longest and largest are best.’ (Archaeologia Cambrensis, 1890)

Related: How To Make DIY Candle Wicks With Cotton String – 3 Ways

What Fat Should I Use For DIY Rushlights?

Rushlights were either dipped in tallow, beexwax or leftover cooking grease, such as leftover bacon fat.

‘The careful wife […] obtains all her fat for nothing. She saves the scummings of her bacon-pot for this use; and if grease abounds with salt, she causes the salt to precipitate to the bottom by setting the scummings in a warm oven. […] about six pounds of grease will dip a pound of rushes […] If men that keep bees will mix a little wax with grease, it will give it a little consistency, and render it more cleanly, and make the rushes burn longer. Mutton-suet will have the same effect.’ (Archaeologia Cambrensis, 1890)

How Long Does A Rushlight Burn?

‘A good rush, which measured in length 2 ft. 4 1/2 in., being minuted, burnt only three minutes short of an hour; and a rush of still greater length has been known to burn one hour and a quarter. […] An experienced old housekeeper assures me that a pound and a half of rushes completely supplies his family the year round, since working people burn no candle in the long days, because they rise and go to bed by daylight. Little farmers use rushes much in the short days, both morning and evening, in the dairy and kitchen’ (Archaeologia Cambrensis, 1890).

‘The length of time a [rush] taper will burn depends upon the angle at which it is set in the candlestick. I find that a well-made taper set at an angle of 45° will burn at the rate of 1 foot in 20 or 30 minutes.’ (Journal, 1886)

Rushlight Vs. Rush Candle

‘The English rushlight, also called rush candle, and Welsh rushlight were different: The English rushlight ‘was a thin tallow candle with a rush wick, placed in a candlestick surrounded for safety by wire gauze; it has long been discarded for the more convenient night-light.

The Welsh rush-light is a taper about 2 feet long, made from the common rush or sedge; the outer skin is peeled off with the exception of a narrow strip left for strength, and the pith is drawn through fat melted in a frying pan or any other suitable vessel. The spongy pith absorbs the fat readily, but it does not receive an outer coating of tallow. It is burnt in a simple candlestick, which holds the taper in any position, and allows it to be shifted readily as it burns down.’ (Journal, 1886)

‘Rushlights and Rush-Candles. – In thrifty times of yore it was a common practice with our peasantry to gather rushes during summer, cut them into the required length, peel off the bark, save a narrow slip left to support the pitch, and after dipping them in fat, lay them by for winter service. These archaic rushlights must not be confounded with the slender candles bearing the same name, formerly purchasable at the chandlers’ shops […] The latter slender candles are the same as ordinary tallow-candles, except that they have a rush in the middle instead of a cotton wick.’ (Archaeologia Cambrensis, 1890)

How To Make Dipped Tallow Rush Candles

‘A truly ancient form of tallow candle is the rushlight. […] A rush, deftly stripped of its skin, of which a slender streak is left to act as a kind of backbone to the tender pith. A number being thus prepared, are allowed to become thoroughly dry, by hanging in an airy loft.

They are then tied by the tops in little bundles of four or six, which are held in the hand, being kept apart by the intervention of the fingers. Thus disposed, they are discreetly immersed in the tallow, of a temperature just high enough to preclude solidification in bulk, yet to insure a sufficient portion adhering to the cold rushes. After two or three dippings, the candle is complete. It remains now to let it harden and whiten, to which end it returns to the aforesaid loft, and in about a months of favourable weather is ready for sale.’ (The Photographic News, 1883)

Related: How To Make Tallow Candles

How To Make DIY Rushlights With Cooking Fat

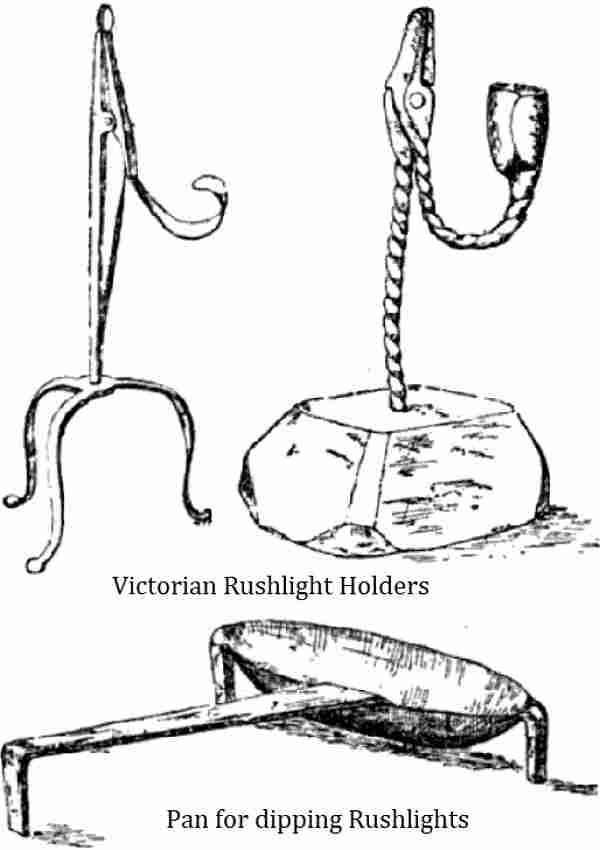

After cutting, the rushes were peeled ‘until nothing remained of the outside rind except a narrow strip of green sufficient to bind together the pith. The rushes when thus prepared and dried were dipped into a vessel called a grisset, containing melted grease, and then dried. The grisset […] was a boat-shaped vessel of metal or iron, standing on three legs, and having a long handle projecting from the centre of the side.’ (Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy, 1891)

‘In some of the country districts the cottagers make rushlights for their own use. […] Rushes were cut in summer or autumn, peeled, dried in the sun, and laid by for winter use. The fat employed was any kind of tallow, skimmings, or fat which the domestic proceedings of the cottage could afford. The rushes were dipped into the melted fat, and each one thus became a rushlight.’ (Reading Lessons, 1858) ‘When the fat is melted, the rushes are “dipped” into or drawn through the scalding fat’ (Archaeologia Cambrensis, 1890).

Rushlight Holders

Rushlight holders were usually made of iron with ‘nozzles or nippers for holding the rushlights, and some have also sockets for holding candles.’ Rushlights ‘were placed in what were termed “rush-sticks,” a homely equivalent of a candlestick, sometimes of iron, at others of wood. […]

The iron holder is somewhat like a pair of ladies’ curling-tongs, with a lump of lead on one of the handle-ends, as a weight to press the blades together when the rush is fixed between them. […] this holder is fixed to a long stick and stand, and is placed, when lighted, by the cottager’s side as he studies his country paper in the evening in the chimney corner of his kitchen or […] fixed to rudely turned beechwood candlesticks, and used upon the supper-table.’ (Gardeners Chronicle & New Horticulturist, 1874)

‘A small deal strip is stuck upright at angles to a broader piece of wood, which acts as a firm basis. The upright board is furnished at the top with a rude iron clamp, which holds the long rush […] at an angle of 30° to the basis, on which the end rests, the ash dropping to the table. A more primitive candlestick and light cannot be conceived.’ (The Photographic News, 1883)

‘A patent rushlight candle lamp was made for beach work and cottage use out of old tumblers, with metal tops and handles added.’ (The Western Antiquary, 1884)

Night Rushlight Holders

Night rushlight holders were ‘in use before the modern night-lights were invented, for keeping with safety a rush-candle burning during the night. It is made of tin, in the form of a cylinder or funnel, about 13 in. high, and 9 1/2 in. in diameter, and within has a socket for a rush-candle. The circumference is pierced with holes three-quarters of an inch in diameter, and 2 in. apart, in twelve rows, each row containing six holes. The rush-candle being placed within the holder for safety, the lines of perforated holes permitted the light to spread over the room.’ (Archaeologia Cambrensis, 1890)

‘The rushlight of our early days will soon become altogether a thing of the past. The “patent nightlights” of modern times have wellnigh supplanted it […] I was told by a farmer that he considered one of the peculiar advanges of the rush-stick to be, that on going to bed you could put the rush at a certain length, get into bed by its light, and then leave it to go out of itself.’ (Gardeners Chronicle & New Horticulturist, 1874)

A night rushlight holder ‘consisted of a cylinder of sheet-iron, perforated with round holes, the cylinder about two feet high. This contained the rushlight. At the bottom was a basin for a little water, that the sparks, as they fell, might be extinguished. […] One always burned at night in my father’s bedroom, and when I was ill I was accommodated with one as well. The feeble, flickering light issued through the perforations and capered in fantastic forms over the walls and furniture. […]

It was necessary in former times for a light to be kept burning all night in one room, for to strike a light was a long and laborious operation. […] Why, a burglar could clear off with the plate before the roused master of the house could strike a light and kindle his candle to look for him.’ (Strange Survivals: Some Chapters in the History of Man, 1894)

Are Rushlights Better Than Candles?

‘Though primitive, the rush-light taper must not be despised, for it possesses certain advantages. In the first place it can be made very cheaply, children can pick and peel the rushes, and the fat used is a product of the farm. All waste fat from sheep or pigs is collected, and when enough has accumulated it is boiled down for use. Secondly, it requires no snuffing like an ordinary tallow candle; and thirdly, no grease drops about when it is carried.’ (Journal, 1886)

‘A piece of rushlight […] well trimmed, gives a remarkably steady light, without flaring or flickering, and is just as intense as that afforded by oil, or tallow, or gas itself […] I do not think a more intense light is got with an Argand lamp [the Argand lamp produced the brightest light in the Victorian era] than with a rushlight, but certainly a far greater quantity of it. ‘ (Microscopic Illustrations of Living Objects, Their Natural History, &c. &c, 1838)

‘A farmer’s dame told us that she always burnt rush candles to work by, in preference to the ordinary candle, on account of the superiority of the light.’ (The Gentleman’s Magazine, 1852) ‘One very good quality of this light is the absence of snuff; the wick consuming as it reaches the air, leaving nothing but a slight feathery ash.’ (The Photographic News, 1883)

The Farthing Rushlight – An Old Story

‘Ralph. […] Damn the rushlight, I can’t put it out, lovee. […]

Tibby. La! Husband, if you can’t manage such a little thing as a rushlight; I am sure you are good for nothing, – Well, I must get up – don’t look – turn your head aside ’till I pin my petticoat round my middle. […] Why, I can’t blow it either.

Ralph. Can’t you manage such a little thing as a rushlight? – He! he! he! – Egad; and you’ll find more difficult things than that. – I must call father. – Here, father, father. Enter Ford in his Shirt.

Ford. What’s the matter? – Eh –

Ralph. We can’t blow out the rushlight […]

Ford. Not blow out the rushlight! That’s strange indeed! Where is it? […] Damn the light, I can’t put it out myself. – Here, neighbour Howard, neighbour Howard. Enter Howard in his Shirt.

Howard. What – what -what – is the house on fire? […]

Ford. Will you be so good as to blow out this rushlight – or damn it, no grand-child, will ever come to light.

Howard. Good heavens! and could none of you blow out a farthing rushlight […] Why, the devil’s in it – what’s to be done? […]

Ralph. Suppose, lovee, you snuff it out with your fingers –

Tibby. I have just washed my hands, dearie, but you may.

Ralph. No, no, lovee, I must not dirty mine, for fear of dirtying you. – Father you can –

Ford. What, with this sore thumb? – No, but neighbour will.

Howard. If I do, d-n me, for I have burnt my fingers more than once already.

Ralph. I have it – I have found out a way […] Egad, I’ll turn it down. (Turns it down, and it goes out

Tibby. Oh, lord, stay till I get into bed –

Howard & Ford. Hold, till I find the door – […] Oh, here’s the door – good night.’ (Ranger’s Repository, 1794)

Please Pin It!

I volunteer for a local arts school that has a community theater. I often make props for the plays, and with Tale of Two Cities coming up, I was going to make a rushlight or two. I plan on just dipping a stick into some wax and provide a battery-powered flame for stage. But, do want to try to make some real rushlights.

After days of looking, I finally found some rushes growing locally. But, I am having a hard time peeling the rushes. I had hoped that the outside would just peel off in long strips. But, they don’t do that. They are fresh-cut, so the outside is still flexible. And I’ve also read in historical writings that they are best harvested late summer. Perhaps the outside is thicker and perhaps peels easier.

The traditional advice is to put them in water to soften them… but presumably this is because they had been harvested in bulk, and are being processed after they have dried out.

Any advice for peeling?

I also thought peeling rushes would be easier! 😉 I peeled fresh rushes but I also put some rushes in water for a couple of days. However, soaking the rushes in water also didn’t make peeling easier in my opinion. But some rushes are easier and some are more difficult to peel. So you can try to find rushes that are easier to peel. 🙂