In the Victorian era, hay was made by hand with a scythe. But even today, a scythe is often used to cut grass and make hay. I love making hay with a scythe – it’s the best full body workout! Every summer, I make hay for our rabbits by hand with a scythe. Besides haymaking, the scythe is also perfect to cut grass on a hill in our garden that is too steep for a lawn mower.

‘Now, whilst the mowers are whetting their scythes, and the fragrant smell of the hay fills the summer air, let us sit on the haycock, and glance at the flowers around us.’ (English Wild Flowers, 1868)

Haymaking Time

‘Spring advances, and soon these blooming pastures must yield their fragrant and nourishing grasses to the mower’s scythe, for no sooner have the fields and hedgerows attained their utmost beauty, than hay-making begins, and hundreds of wild flowers fall at every sweep of the mower’s arm.

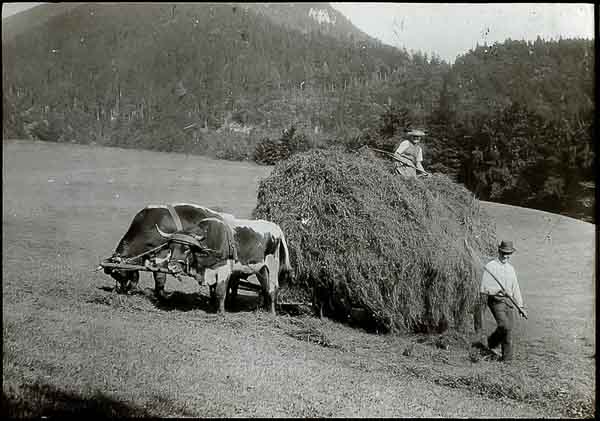

The spreading and tossing of the grass, until it has dried into hay, is usually the pleasant task of men and women with long rakes, who finally gather it into haycocks, and help to load the wagon, which bears it to the rick-yard; but in the neighbourhood of large towns, the process is hastened by the use of the haytedding machine, which is drawn by one horse, and which catches up and tosses about the new hay in a constant whirl.

The variable nature of our climate at the hay-making seasons, makes this a very precarious crop, and when put together in a damp condition, the hay sometimes ferments to such a degree as to take fire.’ (Illustrations of Useful Arts, Manufactures, and Trades, 1858)

Related: Edwardian Haymaking With The Scythe

History Of Haymaking

‘How and when men first learned to make hay will probably never be known, for haymaking is a “process,” and the product is not simply sun dried grass, but grass which has been partly fermented, and is as much the work of men’s hands as flour or cider.

Probably its discovery was due to accident, but possibly man learned it from the pikas, the “calling hares” of the steppes, which cut and stack hay for the winter. That idea would fit in nicely with the theory that central Asia was the “home of the Aryan race” if we were still allowed to believe it, and haymaking is certainly an art mainly practiced in cold countries for winter forage.’ (Healdsburg Tribune, 1904)

History Of The Scythe

‘The first reaping instrument in the world’s history was undoubtedly a straight sword bent into a curved sickle, a form of implement destined to endure from that date to this. With time came improvements. A long handle was added to the curved blade, and the sickle became a scythe’ (Inyo Independent, 1906).

‘The first patent in America was granted to Joseph Jenks, a founder and machinist who had emigrated from Hammersmith, England, where he was bom in 1602. […] n 1635 he patented the present form of the grass scythe, for which he should be held in grateful remembrance.’ (Truckee Republican, 1907)

‘His patent for “ye more speedy cutting of grasse” was renewed for seven years in May, 1655. The improvement consisted in making the blade longer and thinner, and in strengthening it at the same, time by welding a square bar of iron to the back, as in the modern scythe, thus materially improving upon the old English scythe then in use, which was short thick, and heavy, like a bush scythe.’ (Agriculture of the United States in 1860, 1864)

Uses Of The Scythe

Besides haymaking, a scythe can be used for lawn mowing, cutting back weeds like stinging nettles, thistles and brambles, cutting paths into long grass, and harvest wheat – you can even cut shrubs if you use a bush scythe instead of a grass scythe.

A scythe is quieter and even faster than a string trimmer and lawn mower.

‘For a number of years here we cut wheat and barley with the cradle, and laid down four acres of big wheat in a day.’ (Colusa Daily Sun, 1901) ‘Scythe. This implement for mowing grass has been latterly much used for cutting crops, and with great success, when it has been properly mounted with a rake or cradle, and put into expert hands. […] A good mower will cut down with it from an acre and a half to two acres in the day […] The common grass-scythe will cut oats and barley very well when upright’ (The Farmer’s Encyclopædia, and Dictionary of Rural Affair, 1844)

‘About a week after the last strawberry picking I take a scythe and mow the tops off. A short blade is best. Stand on the opposite side of the row to be mown, run the point of the scythe in the ground below the edge, then by a direct swing I cut off all runners and half the tops, keeping the point of the scythe down in order to get the lower ones. After cutting down one side of the row, turn and cut the other side, making a clean cut of the tops and runners. Leave a day until dry, then burn the entire field over if possible, […] otherwise take a horse rake, gather and haul the tops off.’ (Pacific Rural Press, 1905)

‘Lawn is a surface of turf in the vicinity of the house, requiring to be kept smooth by the regular application of the roller and scythe.’ (A Dictionary Of Modern Gardening, 1847) ‘I seldom see anything used but the scythe, in mowing lawns in this country.’ (The Horticulturist, And Journal Of Rural Art And Rural Taste, 1853-74) ‘If we had no lawn to be cut and trimmed, where would be the sounds that most do “rout the brood of care, the sigh of scythe in morning dew”‘ (The Book Of Town & Window Gardening, 1903). ‘The lawn scythe is now but little used, the lawn mower taking its place, unless on hill-sides or among trees or shrubs, where the lawn mower cannot be worked.’ (Gardening For Pleasure, 1883) ‘Strong man to cut grass with a scythe, $2, 9 hours.’ (Los Angeles Herald, 1909)

‘From what has been said, the importance of the lawn in front of the house can be appreciated. It is the rug spread out before the jewel-box. […] An ordinary site will have stones and weeds scattered over it. In the beginning these stones should be carted away and the weeds cut down with a scythe, and a plough run over the surface to a foot in depth’ (The Construction Of The Small House, 1923). ‘Plants of brooksides and ditches should be cut with hoe or scythe in the spring, if they are likely to come within reach of grazing milch cattle.’ (A Manual Of Weeds, 1914)

A Good Scythe

‘A scythe must cut the corn or grass, especially the latter, as near to the ground as possible, and where the land lies flat and the stones have been removed from the surface, a good scythe, in the hands of a skilful mower, will cut the grass so near to the ground that little or no stubble is left. […] it is of the greatest importance that none but the best mowers be entrusted with the work, and that attention be paid to the form of their scythes and to their being frequently whetted. […]

The blades of the scythes on the Continent are mostly made of natural steel, such as is found in parts of Germany, and they are so soft that the edge can be hammered to sharpen it and keep it thin. In England the scythes are forged thin and well tempered, and to prevent their bending they have a rim of iron along the back to within a few inches of the point. This saves much time in sharpening, and they very seldom require the grindstone.

Most scythes have two projecting handles fixed to the principal handle, by which they are held, and these are variously put on […] Hence it is that a man can seldom mow well with another man’s scythe.’ (The Dictionary of the Farm, 1845)

How To Use A Scythe

‘It is the custom in England for the mowers to stoop much in mowing, by which they imagine that they have a wider sweep. […] In other countries mowers stand more upright, and a handle gives them a greater radius. […] it is probable that a man can endure fatigue, and continue his exertion the longer, the more nearly his position is erect.

In some countries the handle of the scythe is nearly straight, and the end of it passes over the upper part of the left arm. The position of the mower is then nearly erect, and his body turns as on a pivot, carrying the blade of the scythe parallel to the ground, and cutting a portion of a considerable circle. […] By turning his body to the right, and stooping towards that side, he begins his cut, and by raising himself up, the muscles of his back greatly assist in swinging the scythe round.’ (The Dictionary of the Farm, 1845)

How To Care For A Scythe

-> Youtube-Video: How To Hone A Scythe Blade

Haymaking

‘The implements used in haymaking by manual labour, or in the methods we have hitherto noticed, are the scythe for cutting, the fork for tedding, and the rake for gathering’ (The Rural Cyclopedia, 1848).

‘Although the genius of modern improvement promises ere long to rob haymaking of one element of the picturesque, it has not yet wholly succeeded in banishing the hand scythe and mower from modern scenery. Tedious and laborious as its use appears compared with that of the mowing machine, it is wonderfully effective in comparison with the rude practice of the Mexican of our day, who cuts his grain and hay by handfulls with a common knife.’ (Agriculture of the United States in 1860, 1864)

‘Grasses and other fodder plants should be cut when the crop has reached its maximum value, in yield and quality, for cured hay; the effect on the aftermath or succeeding crops should also be considered. The main natural function of the plant is to reproduce itself. […] As soon as the flower is fertilized, the seed draws on the store of nourishment in the stems and leaves and the plant begins to harden. […] If cut before the flowers are ripe for fertilization, the plant will renew its efforts to reproduce itself, and the aftermath or second crop will consequently be greater. When cutting is delayed until seeds have started to develop, the natural tendency of Red Clover and other biennial fodder plants is to die down […]

It is usually convenient to cut during that part of the day when the dew prevents the work of making and hauling. […] Tedding or turning the green fodder should commence soon after it is cut. If the crop is heavy, tedding should be continued at intervals until the fodder is sufficiently cured to rake into coils and stack into small cocks. If at all possible, this should be done the day it is cut, or, if cut in the afternoon, the day after.

Green fodder, when cut at the best stage for hay-making, usually contains about eighty per cent of moisture. In good weather even a heavy crop of clover may be dried sufficiently in one day to be ready to put up in small cocks for further curing. The moisture in hay ready to store commonly ranges from twelve to fifteen per cent. A larger percentage would conduce to sweating and mow-burning.

It is a good plan to cut until nine o’clock in the morning and then have one person ted and rake for the balance of the day; hauling and storing should proceed from nine o’clock until four or four-thirty in the afternoon, the remaining two hours or less to be devoted to putting up the freshly cured hay into cocks. Plans for hay-making are, however, often interrupted by showers, which add to the labour of curing and are often more disastrous to the quality of the hay than extreme dry heat.

Even during continued rain it is advisable, by tedding or turning with a fork, to keep the partly cured hay loose and open to prevent it from packing and becoming soaked. Its flavour and much of its nutritive matter are more liable to be lost if it lies in a sodden mass than if it is kept loose and open though wet.

If the weather is dry and hot, it is important to cut and cure promptly. Hay dried by the burning heat of the sun is apt to lose much of its fine quality; it is best shaken out and dried by light winds. In dry, hot weather it is advisable to use the tedder immediately after cutting and at frequent intervals and to rake and cock while the fodder is still quite moist. Rapid ripening sometimes makes it expedient to defer hauling in favour of cutting and curing. It is then advisable to put it up in large cocks.’ (Fodder And Pasture Plants, 1913)

Difficult Haymaking In Rainy & Hilly Areas

‘We have cut hay with the scythe, and had to put it up in a country where rain was to be expected any day; where they bad to scatter it over the ground to dry; where it had to be put up in wind-rows and then in the cock, and scattered out again to dry some more. But it was kept drying as fast as possible, and put under cover as soon as possible.’ (Colusa Daily Sun, 1901)

‘One of the most curious sights that one notices in the agricultural parts of Norway is the peculiar way of drying out the hay. On account of the extreme dampness the grass rots if left on the ground after it is mowed.

Wooden drying fences that stretch for hundreds of yards across the fields are built, and every night the hay is hung out to dry, like the family wash. The sun helps along in the daytime, but it is only a half hearted help, and in the neighborhood of Bergen, where it is said to rain 364 days out of the year, the hay is almost always “on the fence.”

In the lake districts, where the hilly country makes means of transportation very difficult, a heavy copper wire is stretched from the top of a mountain to the village in the valley below. Down this huge masses of hay are sent sailing through the air, sometimes whizzing dangerously near the unwary tourist’s head.’ (San Bernardino Sun, 1906)

Haymaking & Tourists

‘There is one kind of walk that is not popular in Cortina, and the American fondness for short cuts may get you into trouble if you don’t read the signs in your hotel which begs you in three languages not to walk in the fields, those lovely rolling meadows that are one of Cortina’s greatest charms.

Picking wildflowers in the long, waving grasses may be fun for you, but it is very bad for the peasant’s crop of fragrant hay, which is his most precious possession. It seems a shame to mow down such a lovely wild growth, but after scythe and rake have done their work, and the great sweet scented bundles have been carried off on the women’s strong shoulders, you will find that the short velvety green sward is as effective in its own way as the waving meadows.’ (Morning Press, 1907)

Related: Edwardian Picnic Recipes

‘A moonlight picnic given in the height of summer on a night on which a full moon is due as soon as the dusk falls is sure of success […] Such a picnic party might meet at the railway station at half-past six or seven, and on arrival at their destination should take possession of a field where the grass has already been cut, spreading their tablecloth on sloping ground, so that if heat mists rise along the hedges of low-lying fields they may be high above them.’ (Every Woman’s Encyclopaedia, 1910-2)

Edwardian Haymaking Poem

‘Ten little violets with eyes of blue,

Grew on a bank all bathed in dew.

And some were quite short and some were quite tall

But fair and sweet and pure were they all.

Now one of the ten by stretching his head

Could see the daisies, who beck’ning said,

“Come out in the fields, where the bright sunshine

Gleams on the grass and flowers so fine.”

Alas and alas! for they could not go,

Their roots sank deep in the moss below.

But all stretched up on the tip of their toes.

To see the daisies and sweet wild rose.

While looking and sighing, alas, alas,

A man came swinging his scythe through the grass

The bold white daisies and buttercups gay,

Were all soon scattered and withered away.’ (Los Angeles Herald, 1908)

Please Pin It!

I always enjoy learning the history of our customs, as well as skills and craftsmanship from days gone by.

We lived for many years near a community that used these old-fashioned, non-mechanical skills. Fascinating to watch!

Thank you for sharing at this week’s Encouraging Hearts & Home Blog Hop.

Thanks for stopping by, Linda! 😀

As a city girl, I have no idea when I would ever use a scythe to make hay… but I found this article so fascinating! thank you so much for sharing!

Thanks, Kerrie!

I LOVED your article. Sometimes I read things like this and feel as though we’ve totally lost touch with outdoor life.

Thanks so much, Kristie! 😀

My grandfather cut his hay with a scythe. (I guess that shows how old I am . . . ) My mother told me of stories how he would do that and how she would ride a horse that pulled the wagon that he would load the hay on. Then my grandfather would use a hay derrick to put the hay into his barn.

I was glad that my father used a hay swather to cut his hay and a baler to bale it. I drove the tractor that pulled the wagon that my father would load the hay on. Then, we’d go stack the hay in a big haystack by the barn so we could feed the cows.

My grandchildren? Well, we only have 2 acres and don’t grow alfalfa. My grandkids live in a city and don’t have any experience with farming. Sigh.

Lol, I still cut hay with a scythe for our rabbits! 😉 Thanks for stopping by, Nina! 🙂