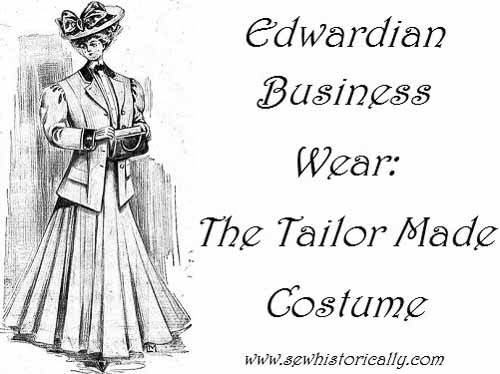

An Edwardian business woman was advised to dress simple, practical, feminine and economical. Her usual dress was either a tailor made wool suit or a shirtwaist costume, which consisted of a dark wool skirt and a white or colored shirtwaist (blouse).

Related: How To Dress In The Edwardian Era

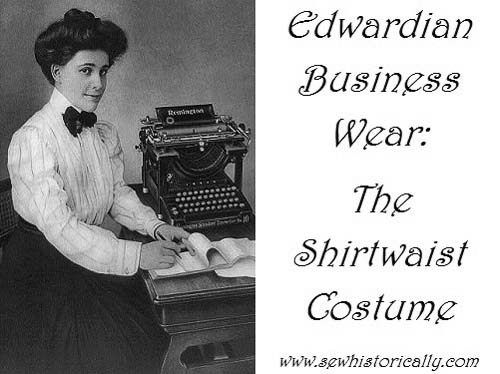

The Shirtwaist Costume

A shirtwaist costume with a black wool skirt and a white shirtwaist is ‘the most suitable dress for the high class office girl’ because ‘the average salary even of this type will not admit of the laundry work necessary to the tailored duck and linen skirts, even in hot weather. […] the black skirt is good looking with a girl’s white shirtwaists if only she have it of lightweight summer stuff, as brilliantine, and if she wear the right kind of hat with it. A black hat should be worn to balance the black skirt and the waist should be immaculate, white collar, white tie, and the best setting plaits. Also the best laundry work. The hat should be all black, too, not a compromise with a rose or something white tucked in under. It may be thin, black crinoline if she fears a somber touch.’ (Chicago Tribune, 1907)

‘As far as the dress is concerned the office girl is not so far off from a uniform style now in the fact that she generally wears a white waist and a black skirt. In the best offices the girls wear a little black apron and white sleeve protectors.’ (Chicago Tribune, 1909)

The Skirt

The skirt should be of good quality, have very little trimming, and should clear the ground. ‘If you be a walking woman and a working woman you should have your skirts to clear the ground’ (Wanganui Chronicle, 1901). The skirt should also have a skirt protector, such as a brush-edge of mohair or velveteen, to protect the hem of the skirt. ‘For summer, light-weight all-wool tweeds, serges, or alpaca’. Linen or cotton frocks only if the laundry costs aren’t too much. For winter, ‘warmer tweed or serge, with a lined skirt’. Skirt and coat shouldn’t have too pronounced fashion features, since a ‘change in fashion would date them too accurately’. (Every Woman’s Encyclopaedia, 1910-2a)

The Shirtwaist

‘There is no one who should be more careful or pay more attention to her appearance than the business woman of today. […] A well-fitted, tailored shirtwaist of some durable material, either a linen or madras, if wash materials are liked; or one of mohair, coleen poplin or a plain dark taffetas, if laundry bills are somewhat a consideration – preferably with a detachable collar, since the collar soils so much sooner than the waist.’ (Los Angeles Herald, 1907)

Variety to the shirtwaist costume comes from a change of blouses, collars, and jabots. Fabrics for the blouse may be ‘delaines, cambrics, simply trimmed’ or made as the ‘more severe’ shirtwaist. ‘Cheap lace trimmings, transparent low yokes and elbow sleeves’ shouldn’t be worn in the office. The cuffs of the blouse should be protected; but paper cuffs may cut the wrist. Better are half-sleeves of cambric or all-over embroidered muslin, fastened with a single pin or elastic. (Every Woman’s Encyclopaedia, 1910-2a)

‘Some arrangement or device to bold the shirtwaist and skirt together is necessary to the trim end trig set around the waist that the present fashion demands […] The safest and best device for preventing what one clever actress refers to as “a 10-minute intermission between her shirtwaist and skirt” is to sew a stout linen tape across the back of the shirtwaist and on this attach two round metal rings, worked over in buttonhole stitch with a heavy sewing cotton. Tbe usual eyes will stretch out with the strain of wear and need renewal too frequently to be worth while. […] Then sew good-sized hooks on the skirt to match, and the threatened intermission will not occur.’ (Los Angeles Herald, 1907)

Jackets And Coats

‘One of the little things that give the stenographer the ‘right look’ is the being particular to wear – or carry – a jacket like her suit. If it is only a little linen coat to her linen suit, let her have it with her.’ (Chicago Tribune, 1907) A blanket cloth or lightweight tweed coat, ‘in some neutral shape’, with or without fur collar is used for cold and rainy days. And a ‘smart and shapely’ cut raincoat of rainproof cloth or mackintosh is a necessity. A knitted woolen jacket or scarf can be worn under the coat on cold days. (Every Woman’s Encyclopaedia, 1910-2b)

Accessories

The most important accessory of an Edwardian business woman is the handbag: ‘It will pay her to get the best leather on account of the wear she gives it and if it is of the newest shape it will add distinction to her appearance as it is the one accessory that she always has with her.

She should be equally particular about her shoes and get the kind without high heels, even if she has to pay more for them.’ (Chicago Tribune, 1907) Weather-proof boots of good leather, not too tight or with narrow or high heels, with rubber overshoes, are ‘the most important item of a business woman’s outfit.’ Hosiery should be of wool, instead of thin openwork stockings. (Every Woman’s Encyclopaedia, 1910-2b)

Her hat ‘should hamonize with her suit and it should not be of a brilliant color. A brilliant red or blue hat is out of place for office wear. Pretty grades of tone can be followed in it, however. Brown could be carried out in many shades until they were as light as champagne color.’ An all white hat shouldn’t be worn, except in hot weather with ‘white duck or tailor made suits.’ ‘Except in the midsummer, let her leave out flowers and trim with ribbons and wings. She can have the most stunning buckles she can get – it always will look remarkably well downtown. A sailor she can have trimmed with flowers, for she should not wear a sailor plain, unless she is extremely young.’ (Chicago Tribune, 1907)

‘Where a touch of color is liked, a little butterfly bow and a ribbon belt to match will serve to relieve the severity of the garb, without in the least detracting from the suitably plain appearance of the design. For example, a very pretty dark blue mohair shirtwaist suit is furnished with sets of cravat and belt. Some are in plaid ribbons, some in pale blue velvet ribbon, while a little made bow tie is matched in a belt of bias armure of a brilliant tone of scarlet, which well sets off the somber tints of the dark blue and does not look in the least out of place, since the little touch of color is but a mere blur.’ (Los Angeles Herald, 1907)

The working woman shouldn’t wear too much jewelry, especially ‘clinking bangles’ (Every Woman’s Encyclopaedia, 1910-2a). Rustling silk petticoats, perfume and cheap as well as expensive jewelry are out of place in the office. (Chicago Tribune, 1907) ‘Day jewelry’, such as belts and buckles, is allowed. (Chicago Tribune, 1909) ‘Of course, the beauty of the girdle depends a great deal upon its buckle or clasp and that is one reason why the article is so expensive. One can buy the material for a handsome fitted girdle for a dollar or so but to purchase a buckle sets the purchaser back $10 or more. There are buckles that are beautiful enough for the handsomest jewel case and the woman who owns these exquisite affairs is as careful of them as of her diamonds.’ (San Francisco Call, 1904)

‘Pretty and necessary ornaments for a swagger shirtwaist effect […] are handsome belt buckles in artistic designs and shirtwaist rings. The stones in these match and the metal may be either gilt or dull silver. As for the gems, are all false and all extremely handsome, as they imitate to a nicety the beautiful false gems of French manufacture. Fifty cents will buy an effective buckle, and one dollar the ring, which is worn on the little finger of the left hand. Shirtwaist rings of pure gold, whose richly colored stones seem really magnificent, cost five dollars each.’ (Sacramento Union, 1909) ‘The shirtwaist ring proper is made of a matrix and costs little. The turquoise ones, with a strong green coloring, are admired, and onyx, artificially colored, has gained a good place.’ (Los Angeles Herald, 1910)

The Hairstyle

The hairstyle of a working woman should be practical without needing ‘constant readjustment’. (Every Woman’s Encyclopaedia, 1910-2a) ‘The pompadour that is up of the face with the least possible swell at the sides and back […] is the one which looks best for most faces, keeps neat and has the best conventional business air. Of course, one has to be governed by faces, but if possible let the downtown girl wear her pompadour without any “dip” at all. For the rest of her hair let her have a coil on top or on the crown of her head. The coil is better than the twisted coronet about not getting out of place and frizzy.’ Puffs and curls are rather for ‘dress coiffures’. Curls ‘are lovely if neat and well done, but they hardly will stand the long day without being taken down or getting frazzled. As to the wave, a little is attractive, but it should be just enough to soften the outlines of the hair – never a stiff marcel such as belongs to formal hair dressing. The plan some business girls follow – having the hair waved Saturday – works well, in that after Sunday the wave looks about right for office wear the rest of the week.’ (Chicago Tribune, 1907)

References:

- Chicago Tribune (1907), How The Working Girl Should Dress, available at http://archives.chicagotribune.com/1907/06/16/page/44/article/how-the-working-girl-should-dress-costumes-designed-by-chicagos-leading-fashion-artists, accessed 22/5/2017

- Chicago Tribune (1909), Should Stenographers Wear Uniforms?, available at http://archives.chicagotribune.com/1909/02/28/page/43/article/should-stenocraphers-wear-uniforms, accessed 17/6/2017

- Every Woman’s Encyclopaedia (1910-2a), Dress For Business Wear, available at http://chestofbooks.com/food/household/Woman-Encyclopaedia-1/Dress-For-Business-Wear.html#.VXmRAEbcB7x, accessed 11/6/2015

- Every Woman’s Encyclopaedia (1910-2b), Dress – Dress For Business Wear, available at http://chestofbooks.com/food/household/Woman-Encyclopaedia-2/Dress-Dress-For-Business-Wear.html#.VXoCHUbcB7z, accessed 11/6/2015

- Los Angeles Herald (1907), The Small Belongings Of Dress And Dressing, available at https://cdnc.ucr.edu/cgi-bin/cdnc?a=d&d=LAH19070317.2.127.7.2&srpos=9&e=——-en–20–1–txt-txIN-shirtwaist+ring——-1, accessed 17/6/2017

- Los Angeles Herald (1910), Worth Knowing, available at https://cdnc.ucr.edu/cgi-bin/cdnc?a=d&d=LAH19101225.2.205.13.1&srpos=1&e=——-en–20–1–txt-txIN-%22shirtwaist+ring%22——-1, accessed 17/6/2017

- Sacramento Union (1909), The Smart Shirtwaist And Odd Bodice Still In Demand, available at https://cdnc.ucr.edu/cgi-bin/cdnc?a=d&d=SU19090425.2.90&srpos=2&e=——-en–20–1–txt-txIN-shirtwaist+ring——-1, accessed 17/6/2017

- Wanganui Chronicle (1901), The Trail Of The Skirt, available at http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=WC19010107.2.5, accessed 11/6/2015

How did they do it? i love it at the same time as love my cotton dress and ballerina pumps i can put on and off i go #bloggerclubuk

I had the more or less same reaction–so much time to get ready, so much money for materials (often from people who had very little), and so restrictive.

It doesn’t take much time to put on Edwardian clothes – I tried it! 😉 And it was a rather cheap outfit – even if the wool was expensive – the wool skirt was worn for maybe ten years or so and later it could be refashioned into another piece of clothing. And cotton fabric for the shirtwaists was cheap.

This post was so interesting! My favorite part was the accessories…”Her hat ‘should hamonize with her suit and it should not be of a brilliant color. A brilliant red or blue hat is out of place for office wear.” I wish we still had hats. They are so classy. Great post!

Thanks so much, Michelle! 😀

Very very nice. I enjoyed reading up on how a woman should dress for the office. In a sense its not changed except women should wear power suits…….LOL.

Thanks, Lee! 🙂

White and black…always a great combination and always in fashion!

That’s right! Thanks for stopping by, Colleen! 🙂