Since millennia, humans and dogs lived together – dogs are the oldest domesticated animal. In ancient times, dogs guarded flocks and farms. Later they were used as hunting dogs. And especially since the 18th century and Victorian era, lap dogs became fashionable. So there’s a long history of dog food. For many centuries, dogs were just fed with barley flour soaked in milk or broth. Then in the 19th century, the first dog biscuits factory opened. But the Edwardians thought dog biscuits weren’t an ideal food: meat mixed with flour or bread and vegetables was considered the best dog food.

Roman Era

In the Roman era (ca. 50 AD) Columella wrote that dogs – there were mainly sheepdogs and guard dogs – can be fed with whey and barley flour, or emmer wheat bread soaked in the liquid of boiled beans (source) (De re rustica – Latin text).

18th Century

‘Barley meal, the dross of wheatflour, or both mixed together, with broth or skim’d milk, is very proper food. For change, a small quantity of greaves from which the tallow is pressed by the chandlers, mixed with their flour ; or sheep’s feet well baked or boiled, are a very good diet, and when you indulge them with flesh it should always be boiled. In the season of hunting your dogs, it is proper to feed them in the evening before, and give them nothing in the morning you take them out, except a little milk. If you stop for your own refreshment in the day, you should also refresh your dogs with a little milk and bread.’ A dog should always have plenty of water, and some twitch grass (couch grass – Elymus repens) on every summer morning. (The Sportsman’s Dictionary, 1785)

Regency/ Georgian Era

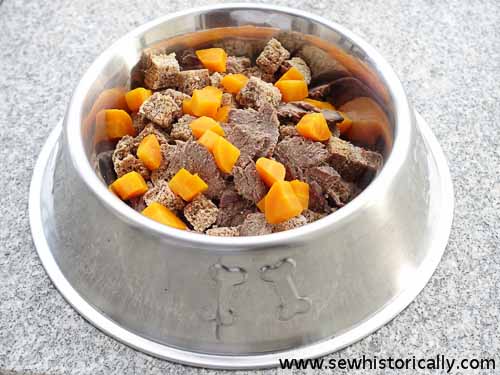

‘The food of the dog, regularly fed, should be two daily portions, however small, of some kind of flesh. With this may be joined farinaceous and vegetable articles – oat-meal, fine-pollard, dog-biscuit, potatoes, carrots, parsnips – soups made from the above, or with sheeps’ heads and trotters.’ (The American Farmer, 1826, p.374)

In 1828, Mr Smith’s dog-biscuit manufactory in the neighborhood of Maidenhead produced five tons dog biscuit a week. (Sporting Magazine, 1828, p. 250)

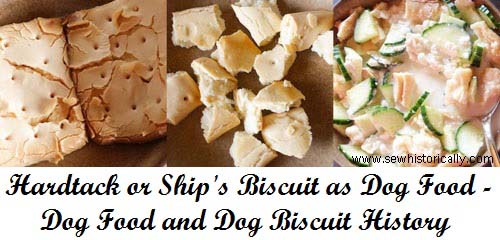

‘The dog is neither wholly carnivorous nor wholly herbivorous, but of a mixed kind, and can receive nourishment from either flesh or vegetables. A mixture of both is therefore his proper food, but of the former he requires a greater portion, and this portion should be always determined by his bodily exertions. […] in some kennels meal and milk are constantly given, and dogs will thrive on this diet during the season they do not hunt’. Wheat meal is the best, while oatmeal and barley meal can occasionally be given when mixed with milk, buttermilk or broth. Potatoes, mixed with milk or buttermilk, are ‘a wholesome food for dogs which are not exercised’. Food can be admixed with ‘greaves, or other fatty matter […] Horse-flesh is a strong, nutritious food for dogs who undergo great exercise’. A dog shouldn’t be fed on raw meat. Dogs near towns can be given ‘tripe, or haunches of sheep’ boiled for half an hour and mixed with French bread raspings […] All kinds of bones, except fish-bones, may be thrown to them at any time’. Vegetables, such as carrots and parsnips, ‘will feed dogs sufficiently well […] Damaged ship-biscuit is often bought for the purpose of food, and it makes a very good one, when soaked in broth or milk.’ After the dog is fed, he ‘should be shut up, to encourage sleep, for digestion is promoted more by sleeping than by waking.’ (The Complete Farrier, and British Sportsman, 1833, p. 428ff)

Victorian Era

‘In the south of England it is much the fashion to give sporting-dogs a food called dog-biscuit instead of barley-meal.’ Barley meal should be ‘varied with bones, for a dog delights to gnaw […] In small private families it is not always possible to obtain a sufficiency of meat and bones for the sustenance of a dog, and recourse is too frequently had to a coarse and filthy aliment, which is highly objectionable, especially if the creature be debarred from taking daily exercise, fettered by a chain, and restricted, by situation, from obtaining access to grass […]

Dog-biscuit is a hard and well-baked mass of coarse, yet clean and wholesome flour, of an inferior kind to that known as sailors’ biscuit; and this latter substance, indeed, would be the best substitute for the former with which we are acquainted. A bag of dog-biscuit of five shillings’ value, will be an ample supply for a yard-dog during the year: it should be soaked in water, or ” pot liquor,” for an hour or two; and if no meat be at hand, a little dripping or lard may be added to it while softening, which will make a relishing meal at a trifling cost.’ (The Quarterly Journal of Agriculture, 1841, p. 244)

In 1861, Spratt patented and began to produce dog biscuits, after he’d watched stray dogs gnawing hardtack at the docks. (source) Here’s an 1876 ad for ‘Spratt’s Patent Meat Fibrine Dog Cakes‘: Spratt’s dog biscuit looks very similar to hardtack.

Edwardian Era

‘Bread cut thin and buttered is suitable for a change and may be given occasionally to all that like it, the slices being broken into small pieces and fed from the hand.

For the heartiest meal of the day – at about six p.m. – boiled rice should be the principal constituent. Over this should be poured a little gravy, and then should be added about one-third as much finely chopped beef or mutton as there is rice, also a small quantity of vegetables, and all the ingredients be thoroughly mixed.

For a change, bread, plain crackers, “tea sops,” beef or mutton broth, and scraps from the table if they are free from grease and pungent condiments, as pepper and mustard. […] With only one small dog in a fairly large family the “scraps” from the table, consisting of trimmings and pieces of stale bread softened with a little gravy, a few spoonfuls of vegetables and small bits of meat should be ample and eminently suitable for his support; but if the dog is of a large size and the family small, or there are several dogs belonging to it, this supply would scarcely meet the demand. Did it nearly do so, however, dog cakes might be used to fill the measure, and they could be depended upon for breakfasts, and given alone and unbroken or crushed and softened with milk or broth.’ (Kennel Secrets: How To Breed, Exhibit And Manage Dogs, 1904)

In 1904, vegetables, such as potatoes, carrots, parsnip and beetroot, are considered beneficial as part of the dog food; while greens, such as the tops of turnips, nettles and dandelion, ‘favor the digestion of “hearty” foods’. Vegetables ‘should be as fresh and free from taint as those on the table’. Farinaceous substances, bread-stuffs or starchy foods, are also good as part of a dog’s diet. Wheat is the best, ‘containing as it does the most flesh-forming and energy-producing materials […] dogs can subsist upon it alone for a long time and retain health and vigor, provided they are allowed all parts of the grain’.

White bread is ‘practically valueless’, while brown bread might be given: ‘bread remnants if untainted are all very well in their way, for when softened with broths and mixed with meat they render these foods more digestible as well as slightly more nutritious; at the same time they harmlessly increase the quantity – a matter of no little importance in using highly concentrated foods which would scarcely satisfy the appetite of the average dog unless more than he could properly assimilate was allowed. […] As for “brown bread” proper, called Graham bread by many, it is decidedly richer in nutritive matters than the white bread, for it contains all parts of the wheat grain.’ Graham bread contains the indigestible bran which aids digestion. Graham bread ‘may be given with meat alone, in about the proportion of three parts bread to one of meat, or mixed with other starchy foods – as for instance, one-half “brown bread,” one-fourth rice, one-fourth meat, and perhaps one or two eggs, the bread being softened always with a little broth, and the meat chopped fine and well mixed with it and the other foods.’ Boston brown bread is of less value than Graham bread and ‘should only be given them after it has been long baked or kept until it is dry and hard’. ‘Bread trimmings are quite extensively used in kennels, they being obtainable in cities of dealers who contract for them with keepers of hotels, restaurants, etc., and sell them for much less than the cost of their ingredients.’ (Kennel Secrets: How To Breed, Exhibit And Manage Dogs, 1904, part 1 to 2)

It’s ‘absolutely necessary’ to cook maize or Indian corn meal ‘for at least three hours, otherwise it will be highly indigestible and much of it will journey through the intestinal canal and pass out unchanged in the discharges, and possibly cause diarrhoea.’ Cooking maize meal is a laborious process ‘for unless it is stirred constantly it is quite sure to burn’. But corn flour can also be baked as corn cakes together with ‘meat, either cooked or raw, “beef-flour” or cracklings’ in an hot oven for several hours or overnight, and can be served as evening meal. Oatmeal and barley can also be given occasionally, but, like corn flour, it has to be cooked for three hours at least – oatmeal with broth or milk, and barley with meat. ‘Rice is extremely poor in tissue-building and energy-producing matters, being very nearly pure starch, yet it is by no means to be despised […] When properly cooked it is digested with the greatest ease, hence is well borne even where the digestive organs are disordered.’ Rye shouldn’t be given alone, and it’s rather for ‘hardy dogs that are given a very great amount of exercise every day.’ (Kennel Secrets: How To Breed, Exhibit And Manage Dogs, 1904, part 3 to 4)

‘Regarding the so-called “dog cakes” or “dog biscuits,” since the first edition of this book their manufacture has become such an industry and the competition so great, they are not generally of a quality deserving commendation, as formerly. They are a very good accessory food; but the claim that any brand constitutes or is a near approach to an ideal food is a rank absurdity. They are said to contain beef, and yet the writer has never been able to find even a trace of any during his analyses. They are practically bread, and possibly have nearly the nutritive value of what is known as “graham bread” of the table. Over that and other breads they possess an advantage, however, the result of their being so long and thoroughly cooked. […]

While in an emergency – for a few days – they could be relied on as the sole food, the rule should be to feed them with other foods. To dogs with good sound teeth they might be given whole occasionally, but not invariably, nor to very young or old dogs, for their teeth would likely break or be otherwise injured. It should be the custom to crush them; and if one has not a machine for the purpose, a good method is to put a few into a strong bag and pound them with a mallet or hammer. Thus broken up well, they may be used to thicken milk, broths, or soups, or mixed with meat.’ (Kennel Secrets: How To Breed, Exhibit And Manage Dogs, 1904, part 4)

WW1 Era

Most dog bread is mainly made of flour and the ‘waste portions of meat and tallow, including the skin and fiber, […] imported from South American tallow factories in the form of blocks. […] Wheat flour, containing as little bran as possible, is generally used, oats, rye, or Indian meal being only mixed in to make special varieties, or, as in the case of Indian meal, for cheapness. Rye flour would give a good flavor, but it dries slowly, and the biscuits would have to go through a special process of drying after baking, else they would mold and spoil. Dog bread must be made from good wheat flour, of a medium sort, mixed with 15 or 16 per cent of sweet, dry chopped meat, well baked and dried like pilot bread or crackers. This is the rule for all the standard dog bread on the market. There are admixtures which affect more or less its nutritive value, such as salt, vegetables, chopped bones, or bone meal, phosphate of lime, and other nutritive salts. In preparing the dough and in baking, care must be taken to keep it light and porous.’ (Henley’s Twentieth Century Formulas, Recipes And Processes, 1916)

‘Dogs should have plain food, but don’t be afraid of giving them some meat once a day, cooked, and cut up small, avoiding fat, and also not feeding veal or pork, neither of which are good for dogs, beef and mutton are both good – we eat meat every day, and why not our dogs. Never feed lights, not digestible, and you might as well feed leather. Cooked liver is always relished by a dog, and once a week of cooked liver is a treat’ but it shouldn’t be given too often. Sour milk and buttermilk is better than milk, ‘and in summer time I give my dogs all around, some buttermilk as an “extra.’ once a week.’ (Everything About The Dogs, 1917)